The Story Behind The Most Daring Picture Book I’ve Ever Written, Goodnight Litttle Man: The Lost and Found Child

My latest book, Goodnight Little Man, is the most ambitious picture book I’ve ever published. It tackles Social Emotion Learning, child psychology, and multiracial/generational families. This book is unique, the first of its kind.

One could say that if the books Knuffle Bunny, Llama Llama Red Pajama, Goodnight Moon, Where the While Things Are, and The Whole Brain Child all had a baby, that child would be Goodnight Little Man.

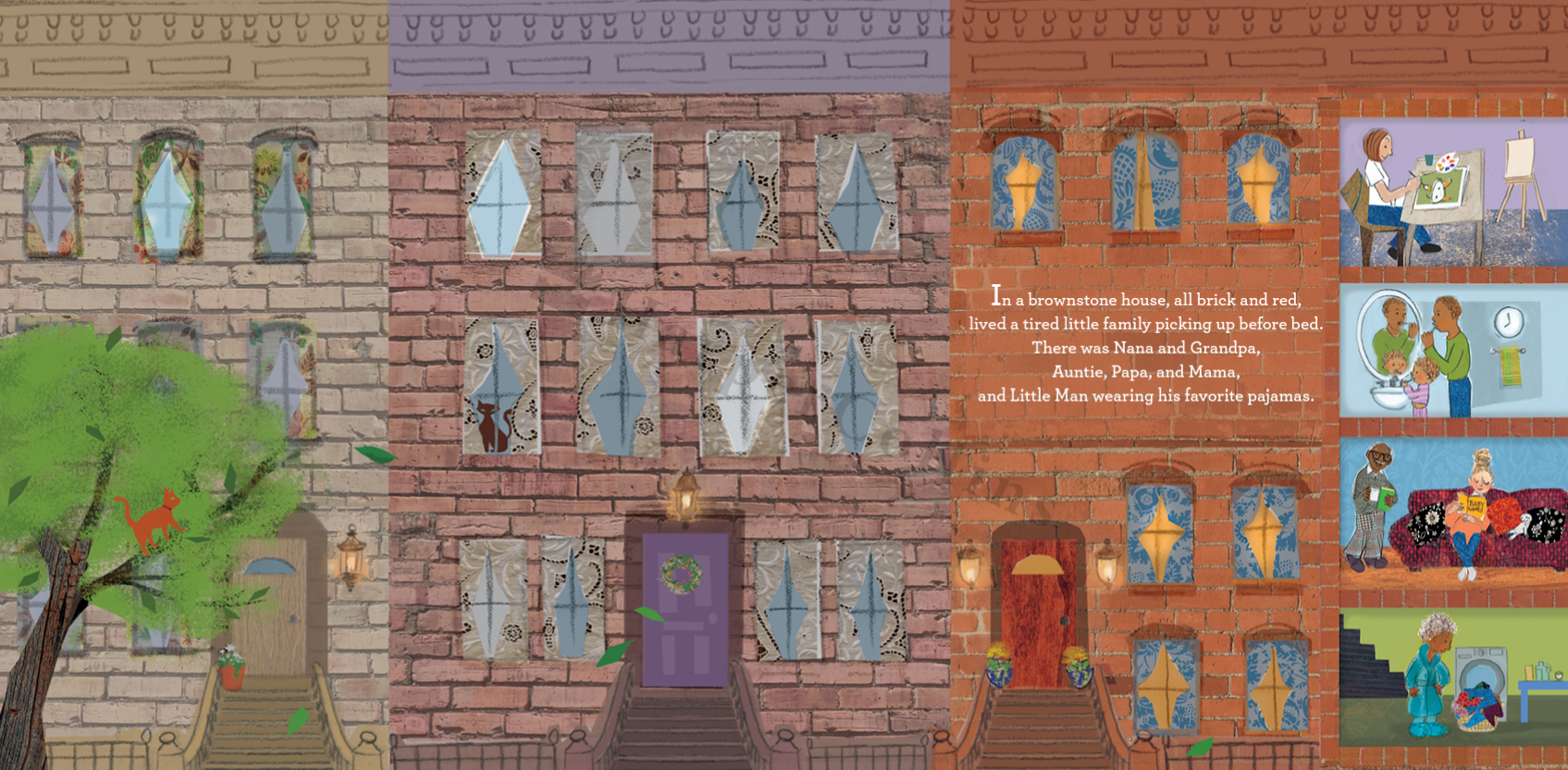

Goodnight Little Man is about a little boy who loses his comfort animal, Sheep-Sheep, and goes on a search-and-rescue mission around the house. On his journey, he meets the many members of his multigenerational/multiracial home. How many books show multiracial couples, multiracial families, and multigenerational families living together? Few. But it happens. It happened in our home.

Goodnight Little Man rhymes. It is one of the most straightforward rhyming books I’ve written. Yet, many will either love or hate the Bernstroming of the meter and the use of near rhymes and chiming in the text. Yet, I hope that the simple meter lulls the reader into a sleepy security... that is, until it doesn’t! Read on to find out more.

The artistic nuances Sheffield put in the book abound. Heidi Sheffield is a collage artist. There are layers upon layers in her art. For example, I wonder how many will discover that the hidden key that unlocks this book is on the first page. My wife spotted it right away. You see, Heidi Sheffield (the illustrator and I) discussed the book several times as she illustrated. She asked for my input, and I asked for her. In the book, you see the author and illustrator working hand in hand to create a book that works with the reader for the reader. Words and images are braided. So it happened that, on the first page, a child could know where the missing sheep was. That’s a story trick from Toni Morrison. Give the story away on the first page.

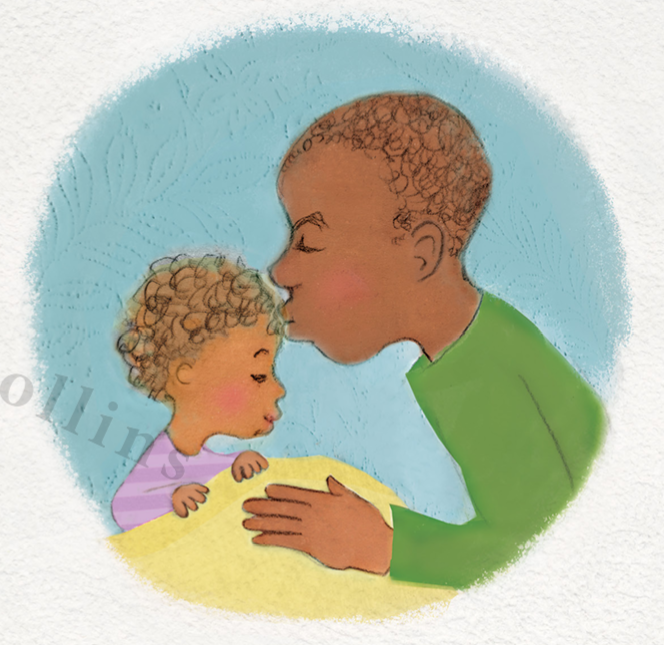

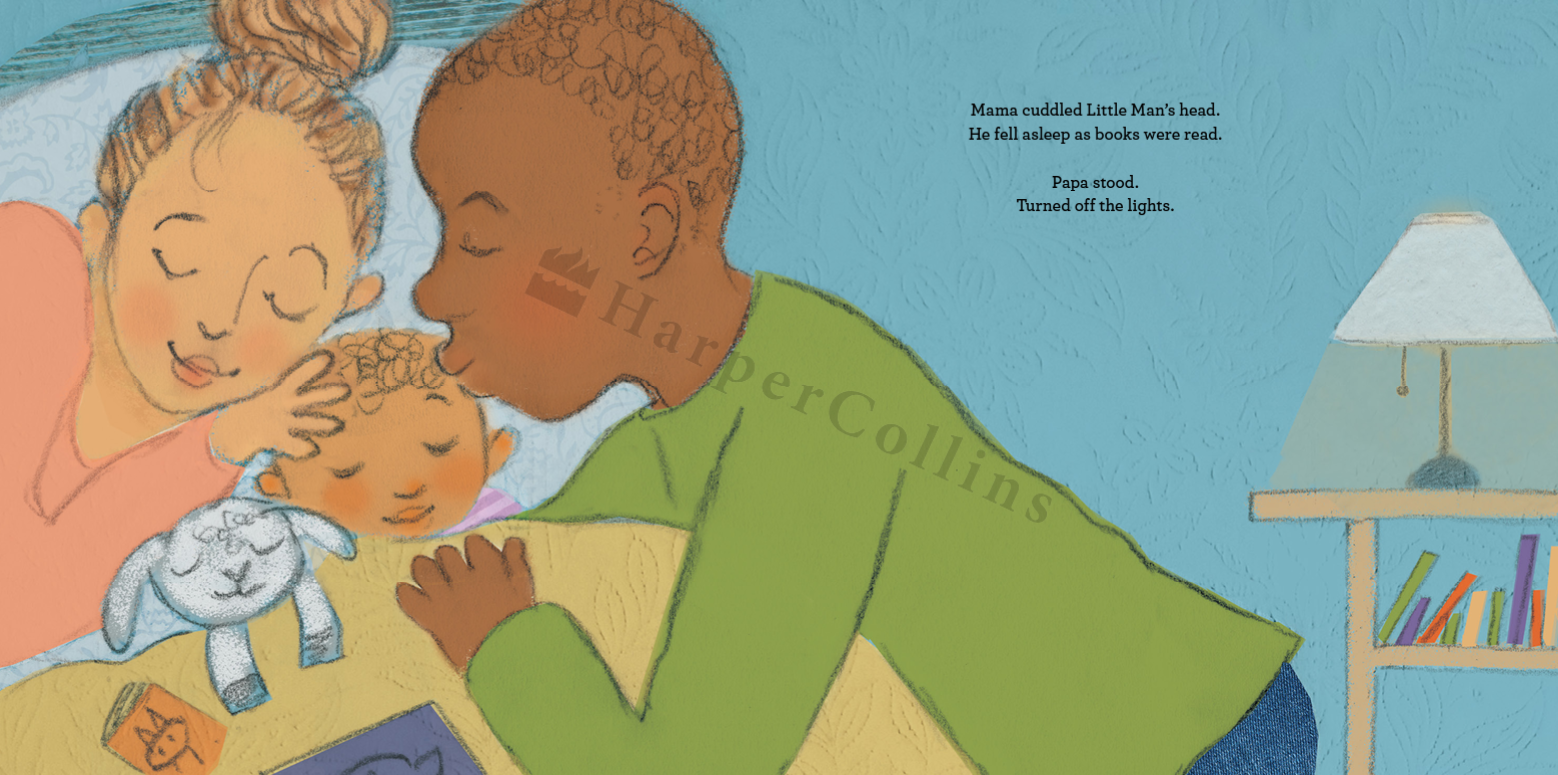

And so Little Man goes on his journey to find his lost sheep. He meets Grandpa, Nana, Auntie, and Papa. But why did I choose to leave Mama out? Why did I decide to leave Mama last? I did it on purpose, and Sheffield immediately picked up on it. You see, everyone helps Little Man look for Sheep-Sheep, including Papa. Everyone, that is, except Mama. Where is she? We know she’s there because we see her on the first page. But on the very next page, Mama is missing, and it is Papa kissing Little Man goodnight. Therefore, the reader should ask: Why not Papa and Mama? Bingo! It’s a minor detail, but imagine if a child usually goes to bed saying goodnight to both Mama and Papa. Suddenly, things are different. Something is wrong.

In story structure, we often talk about the two plots in every story. One is the external plot--Little Man must find Sheep-Sheep. And then there is the internal plot--Why does Little Man need to find Sheep-Sheep? Little Man gives it away when he’s talking to Papa.

“No,” said Little Man

“Excuse me, son?”

“No,” said Little Man. “We can’t be done.”

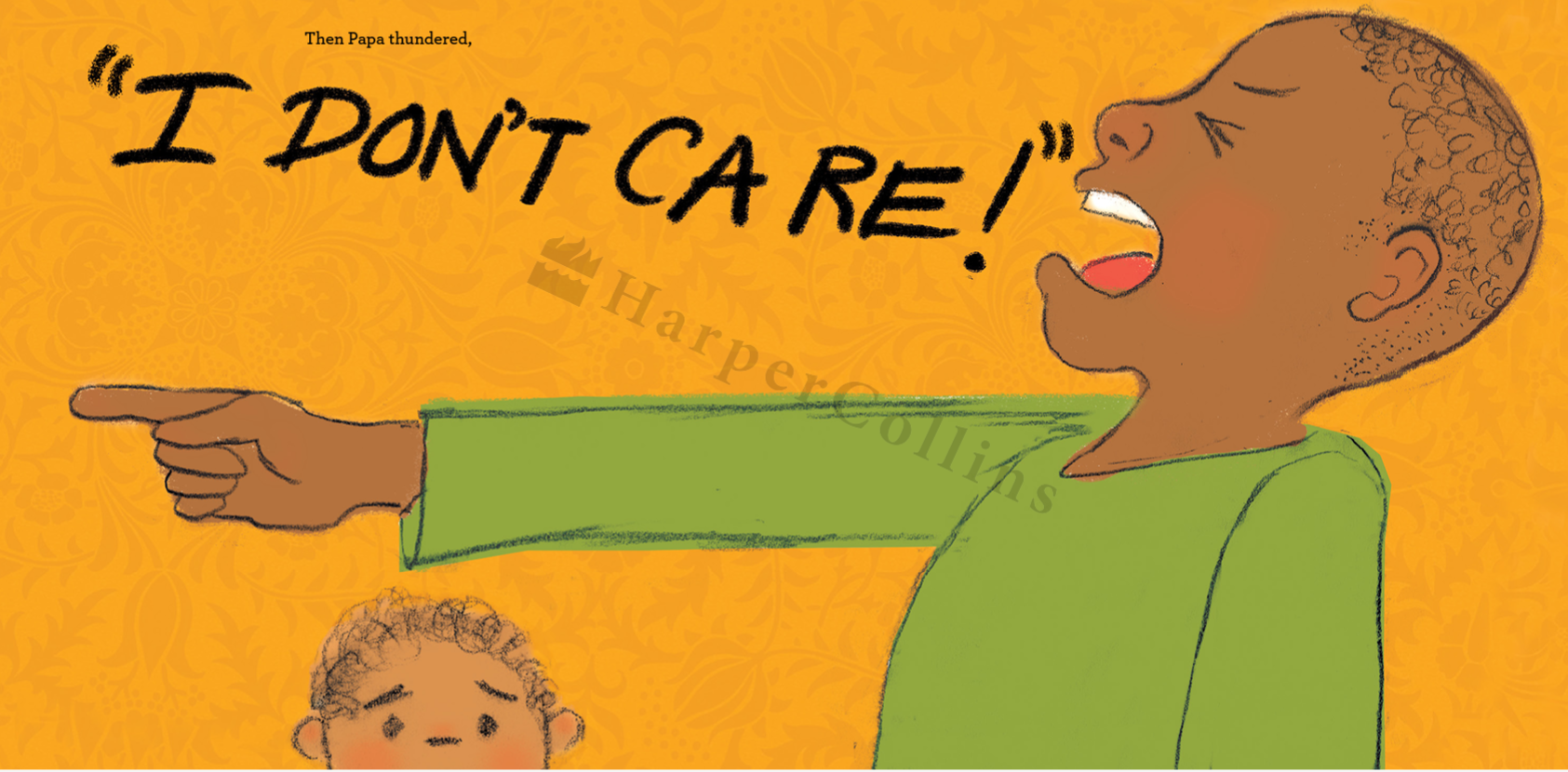

Then Papa used his upset voice:

“Go back to bed, and no more noise!”

“But Papa, Papa! Sheep-Sheep’s scared.”

The Papa thundered, “I DON’T CARE!”

Did you catch it? Little Man said that Sheep-Sheep was scared. When a child indicates that something else is scared, they often mean that they are the ones who are afraid. But why is Little Man afraid? Something is wrong. Something is not right. Something needs to be fixed. And the reader should still be wondering, WHERE IS MAMA?!

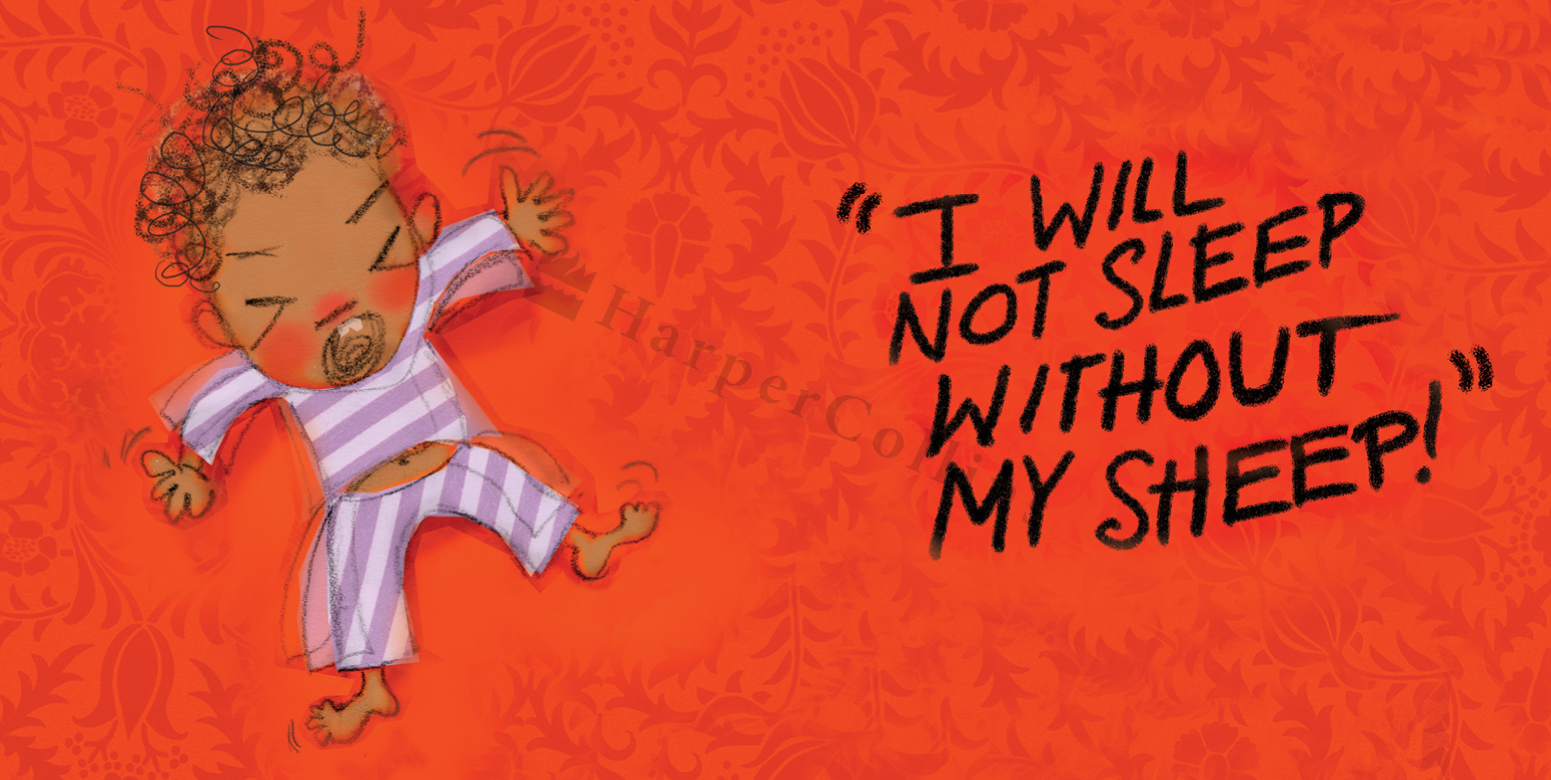

Now, back to the conflict between Little Man and Papa. Papa shouting at his son, thundering, “I DON’T CARE!” doesn’t go over well. Little Man mirrors Papa’s rage. He reflects Papa’s lack of emotional regulation. This is what I learned from reading the work of Dr. Tina Payne Bryson and Daniel Siegel. And Papa’s anger is more than matched by Little Man’s own, and the tantrum is one for the ages.

Now, I can see some being upset at me for showing a father shouting at his son, but it’s an honest fact that parents aren’t perfect (as much as we long to be). Dr. Tina Payne Bryson talks about the “Rupture-and-Repair” process in parenting. She essentially says, Yep, parenting is hard, and you’re going to make mistakes, but when you mess up and rupture the relationship, move quickly to repair it. How many picture books demonstrate this much-needed truth? Where the Wild Things Are is perhaps the best example. Max’s mother ruptures the relationship by sending him to bed without supper. Then she feels terrible. He feels bad too. She puts a bowl of soup in his room. She is trying to repair the relationship. Rember, it was the soup that brought Max back home from a land of monsters. That’s Rupture and Repair in a nutshell. Yes, it was done with monsters, but we still need books that face Rupture and Repair head-on. It matters to kids and parents. To quote the New York Times on how divisive Where the Wild Things Are was:

“Wild Things” is one of the few books in the children's field, and perhaps the only one, that acknowledges with any compassion the child's burden of rage and frustration and allows him, with affection and humor, to discharge it. “‘Wild Things’ split the Establishment,” di Capua recalls. “There were people who were horrified when it won the Caldecott. They pinned their objections on the monsters, but they really objected to knowing that children get angry at their mothers. These are the people who tend to sentimentalize childhood, to be overprotective. Maurice has almost single‐handedly opened a door on another word.”

Little Man’s tantrum and the waking of Mama (who had fallen asleep on the couch) are the catalysts that begin the ultimate repair he’s looking for. The story builds to the foremost thing Little Man was looking for all along. Mama. Why? Well, it’s never said, but Sheffield brilliantly illustrates a pregnant mom sleeping with Sheep-Sheep on the couch. Papa is clearly trying to do his best without his partner, but he’s stumbling, fumbling, failing. In trying to allow his sleeping wife to rest, he’s blown up bedtime. Perhaps she was picking up Sheep-Sheep to bring it to Little Man, or maybe she was going to give it to Dad. All we know is that she fell asleep with the precious Sheep-Sheep.

At the end of the book, Little Man is no longer scared. And though it seems like Little Man isn’t anxious or nervous at the beginning of the book, he is. My kids do all kinds of things to avoid falling asleep, such as going to the bathroom a billion times, looking for a book, asking for a story, AND asking Heather and then me to rub their backs. They put off sleep because they are afraid of the dark, anxious about dreams, or worried about waking up alone. See what I mean about child psychology? All of this is there in the pages of this little book. It’s in the words and the art; you won’t notice all this at first. Good. But it’s there. Images were not haphazard; words and sequence were painstakingly chosen to create a beautiful story of a child’s desire to say, I love you to everyone before bed.

The last page of the book brings the reader full circle. We begin where we end. The hero has gone on his journey, vanquished his villain, and rescued his sheep, but he’s found the true treasure he was looking for all along. Bedtime is back to normal. Mama and Papa are there together with him. He’s safe. Not forgotten. Not lost. He’s not lost. Not lost in a busy family. Not lost as he awaits the new baby. Mama knows right where he is and what he needs, and Papa (who also feels lost) has repaired the relationship.

Little Man was lost, but now he is found.